Introduction

This handbook is a guide to ordinal theory. Ordinal theory concerns itself with satoshis, giving them individual identities and allowing them to be tracked, transferred, and imbued with meaning.

Satoshis, not bitcoin, are the atomic, native currency of the Bitcoin network. One bitcoin can be sub-divided into 100,000,000 satoshis, but no further.

Ordinal theory does not require a sidechain or token aside from Bitcoin, and can be used without any changes to the Bitcoin network. It works right now.

Ordinal theory imbues satoshis with numismatic value, allowing them to be collected and traded as curios.

Individual satoshis can be inscribed with arbitrary content, creating unique Bitcoin-native digital artifacts that can be held in Bitcoin wallets and transferred using Bitcoin transactions. Inscriptions are as durable, immutable, secure, and decentralized as Bitcoin itself.

Other, more unusual use-cases are possible: off-chain colored-coins, public key infrastructure with key rotation, a decentralized replacement for the DNS. For now though, such use-cases are speculative, and exist only in the minds of fringe ordinal theorists.

For more details on ordinal theory, see the overview.

For more details on inscriptions, see inscriptions.

When you're ready to get your hands dirty, a good place to start is with inscriptions, a curious species of digital artifact enabled by ordinal theory.

Links

- GitHub

- BIP

- Discord

- Open Ordinals Institute Website

- Open Ordinals Institute X

- Mainnet Block Explorer

- Signet Block Explorer

Videos

- Ordinal Theory Explained: Satoshi Serial Numbers and NFTs on Bitcoin

- Ordinals Workshop with Rodarmor

Ordinal Theory Overview

Ordinals are a numbering scheme for satoshis that allows tracking and transferring individual sats. These numbers are called ordinal numbers. Satoshis are numbered in the order in which they're mined, and transferred from transaction inputs to transaction outputs first-in-first-out. Both the numbering scheme and the transfer scheme rely on order, the numbering scheme on the order in which satoshis are mined, and the transfer scheme on the order of transaction inputs and outputs. Thus the name, ordinals.

Technical details are available in the BIP.

Ordinal theory does not require a separate token, another blockchain, or any changes to Bitcoin. It works right now.

Ordinal numbers have a few different representations:

-

Integer notation:

2099994106992659The ordinal number, assigned according to the order in which the satoshi was mined. -

Decimal notation:

3891094.16797The first number is the block height in which the satoshi was mined, the second the offset of the satoshi within the block. -

Degree notation:

3°111094′214″16797‴. We'll get to that in a moment. -

Percentile notation:

99.99971949060254%. The satoshi's position in Bitcoin's supply, expressed as a percentage. -

Name:

satoshi. An encoding of the ordinal number using the charactersathroughz.

Arbitrary assets, such as NFTs, security tokens, accounts, or stablecoins can be attached to satoshis using ordinal numbers as stable identifiers.

Ordinals is an open-source project, developed on GitHub. The project consists of a BIP describing the ordinal scheme, an index that communicates with a Bitcoin Core node to track the location of all satoshis, a wallet that allows making ordinal-aware transactions, a block explorer for interactive exploration of the blockchain, functionality for inscribing satoshis with digital artifacts, and this manual.

Rarity

Humans are collectors, and since satoshis can now be tracked and transferred, people will naturally want to collect them. Ordinal theorists can decide for themselves which sats are rare and desirable, but there are some hints…

Bitcoin has periodic events, some frequent, some more uncommon, and these naturally lend themselves to a system of rarity. These periodic events are:

-

Blocks: A new block is mined approximately every 10 minutes, from now until the end of time.

-

Difficulty adjustments: Every 2016 blocks, or approximately every two weeks, the Bitcoin network responds to changes in hashrate by adjusting the difficulty target which blocks must meet in order to be accepted.

-

Halvings: Every 210,000 blocks, or roughly every four years, the amount of new sats created in every block is cut in half.

-

Cycles: Every six halvings, something magical happens: the halving and the difficulty adjustment coincide. This is called a conjunction, and the time period between conjunctions a cycle. A conjunction occurs roughly every 24 years. The first conjunction should happen sometime in 2032.

This gives us the following rarity levels:

common: Any sat that is not the first sat of its blockuncommon: The first sat of each blockrare: The first sat of each difficulty adjustment periodepic: The first sat of each halving epochlegendary: The first sat of each cyclemythic: The first sat of the genesis block

Which brings us to degree notation, which unambiguously represents an ordinal number in a way that makes the rarity of a satoshi easy to see at a glance:

A°B′C″D‴

│ │ │ ╰─ Index of sat in the block

│ │ ╰─── Index of block in difficulty adjustment period

│ ╰───── Index of block in halving epoch

╰─────── Cycle, numbered starting from 0

Ordinal theorists often use the terms "hour", "minute", "second", and "third" for A, B, C, and D, respectively.

Now for some examples. This satoshi is common:

1°1′1″1‴

│ │ │ ╰─ Not first sat in block

│ │ ╰─── Not first block in difficulty adjustment period

│ ╰───── Not first block in halving epoch

╰─────── Second cycle

This satoshi is uncommon:

1°1′1″0‴

│ │ │ ╰─ First sat in block

│ │ ╰─── Not first block in difficulty adjustment period

│ ╰───── Not first block in halving epoch

╰─────── Second cycle

This satoshi is rare:

1°1′0″0‴

│ │ │ ╰─ First sat in block

│ │ ╰─── First block in difficulty adjustment period

│ ╰───── Not the first block in halving epoch

╰─────── Second cycle

This satoshi is epic:

1°0′1″0‴

│ │ │ ╰─ First sat in block

│ │ ╰─── Not first block in difficulty adjustment period

│ ╰───── First block in halving epoch

╰─────── Second cycle

This satoshi is legendary:

1°0′0″0‴

│ │ │ ╰─ First sat in block

│ │ ╰─── First block in difficulty adjustment period

│ ╰───── First block in halving epoch

╰─────── Second cycle

And this satoshi is mythic:

0°0′0″0‴

│ │ │ ╰─ First sat in block

│ │ ╰─── First block in difficulty adjustment period

│ ╰───── First block in halving epoch

╰─────── First cycle

If the block offset is zero, it may be omitted. This is the uncommon satoshi from above:

1°1′1″

│ │ ╰─ Not first block in difficulty adjustment period

│ ╰─── Not first block in halving epoch

╰───── Second cycle

Rare Satoshi Supply

Total Supply

common: 2.1 quadrillionuncommon: 6,929,999rare: 3437epic: 32legendary: 5mythic: 1

Current Supply

common: 1.9 quadrillionuncommon: 808,262rare: 369epic: 3legendary: 0mythic: 1

At the moment, even uncommon satoshis are quite rare. As of this writing, 745,855 uncommon satoshis have been mined - one per 25.6 bitcoin in circulation.

Names

Each satoshi has a name, consisting of the letters A through Z, that get shorter the further into the future the satoshi was mined. They could start short and get longer, but then all the good, short names would be trapped in the unspendable genesis block.

As an example, 1905530482684727°'s name is "iaiufjszmoba". The name of the last satoshi to be mined is "a". Every combination of 10 characters or less is out there, or will be out there, someday.

Exotics

Satoshis may be prized for reasons other than their name or rarity. This might be due to a quality of the number itself, like having an integer square or cube root. Or it might be due to a connection to a historical event, such as satoshis from block 477,120, the block in which SegWit activated, or 2099999997689999°, the last satoshi that will ever be mined.

Such satoshis are termed "exotic". Which satoshis are exotic and what makes them so is subjective. Ordinal theorists are encouraged to seek out exotics based on criteria of their own devising.

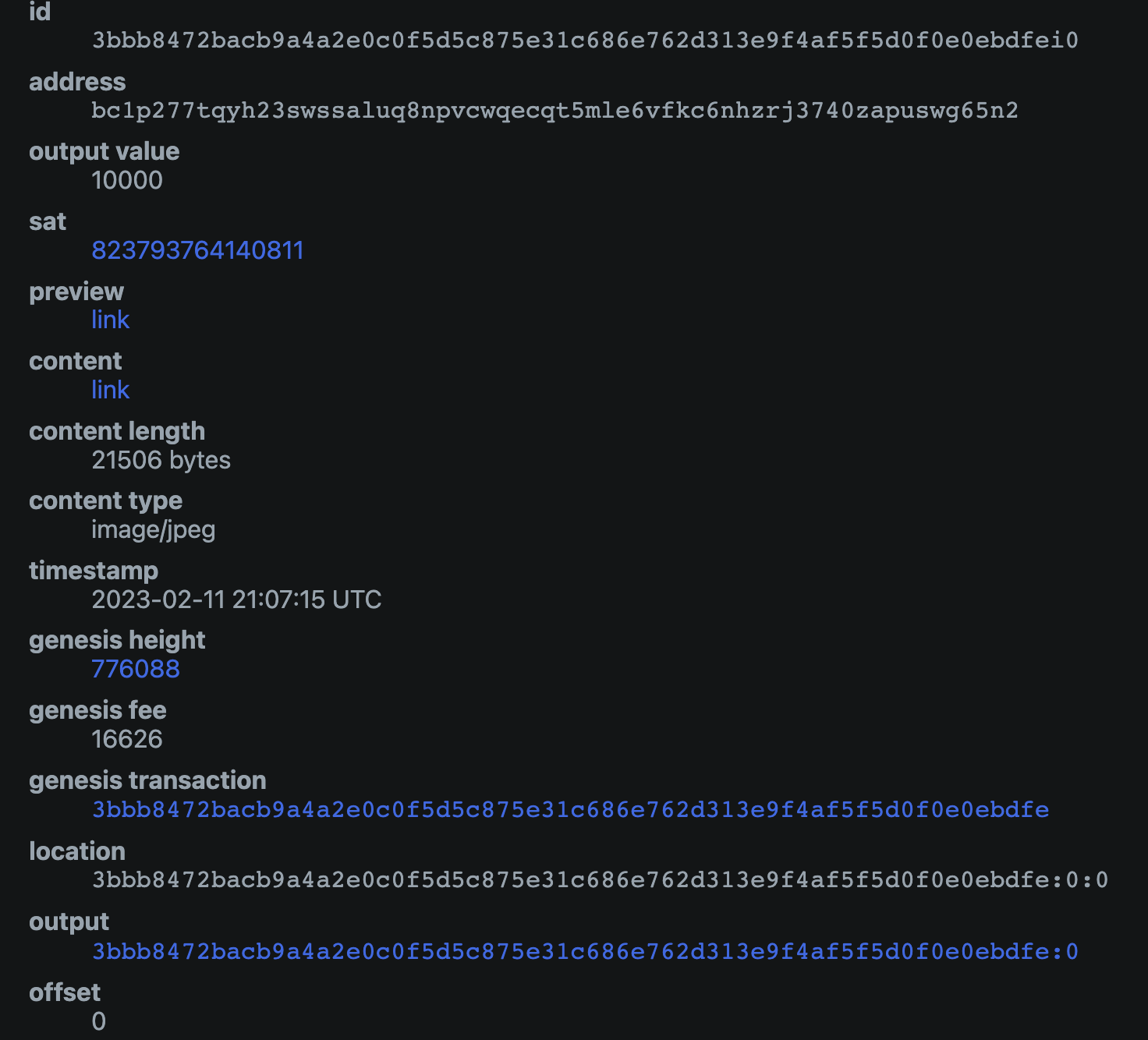

Inscriptions

Satoshis can be inscribed with arbitrary content, creating Bitcoin-native digital artifacts. Inscribing is done by sending the satoshi to be inscribed in a transaction that reveals the inscription content on-chain. This content is then inextricably linked to that satoshi, turning it into an immutable digital artifact that can be tracked, transferred, hoarded, bought, sold, lost, and rediscovered.

Archaeology

A lively community of archaeologists devoted to cataloging and collecting early NFTs has sprung up. Here's a great summary of historical NFTs by Chainleft.

A commonly accepted cut-off for early NFTs is March 19th, 2018, the date the first ERC-721 contract, SU SQUARES, was deployed on Ethereum.

Whether or not ordinals are of interest to NFT archaeologists is an open question! In one sense, ordinals were created in early 2022, when the Ordinals specification was finalized. In this sense, they are not of historical interest.

In another sense though, ordinals were in fact created by Satoshi Nakamoto in 2009 when he mined the Bitcoin genesis block. In this sense, ordinals, and especially early ordinals, are certainly of historical interest.

Many ordinal theorists favor the latter view. This is not least because the ordinals were independently discovered on at least two separate occasions, long before the era of modern NFTs began.

On August 21st, 2012, Charlie Lee posted a proposal to add proof-of-stake to Bitcoin to the Bitcoin Talk forum. This wasn't an asset scheme, but did use the ordinal algorithm, and was implemented but never deployed.

On October 8th, 2012, jl2012 posted a scheme to the same forum which uses decimal notation and has all the important properties of ordinals. The scheme was discussed but never implemented.

These independent inventions of ordinals indicate in some way that ordinals were discovered, or rediscovered, and not invented. The ordinals are an inevitability of the mathematics of Bitcoin, stemming not from their modern documentation, but from their ancient genesis. They are the culmination of a sequence of events set in motion with the mining of the first block, so many years ago.

Digital Artifacts

Imagine a physical artifact. A rare coin, say, held safe for untold years in the dark, secret clutch of a Viking hoard, now dug from the earth by your grasping hands. It…

…has an owner. You. As long as you keep it safe, nobody can take it from you.

…is complete. It has no missing parts.

…can only be changed by you. If you were a trader, and you made your way to 18th century China, none but you could stamp it with your chop-mark.

…can only be disposed of by you. The sale, trade, or gift is yours to make, to whomever you wish.

What are digital artifacts? Simply put, they are the digital equivalent of physical artifacts.

For a digital thing to be a digital artifact, it must be like that coin of yours:

-

Digital artifacts can have owners. A number is not a digital artifact, because nobody can own it.

-

Digital artifacts are complete. An NFT that points to off-chain content on IPFS or Arweave is incomplete, and thus not a digital artifact.

-

Digital artifacts are permissionless. An NFT which cannot be sold without paying a royalty is not permissionless, and thus not a digital artifact.

-

Digital artifacts are uncensorable. Perhaps you can change a database entry on a centralized ledger today, but maybe not tomorrow, and thus one cannot be a digital artifact.

-

Digital artifacts are immutable. An NFT with an upgrade key is not a digital artifact.

The definition of a digital artifact is intended to reflect what NFTs should be, sometimes are, and what inscriptions always are, by their very nature.

Inscriptions

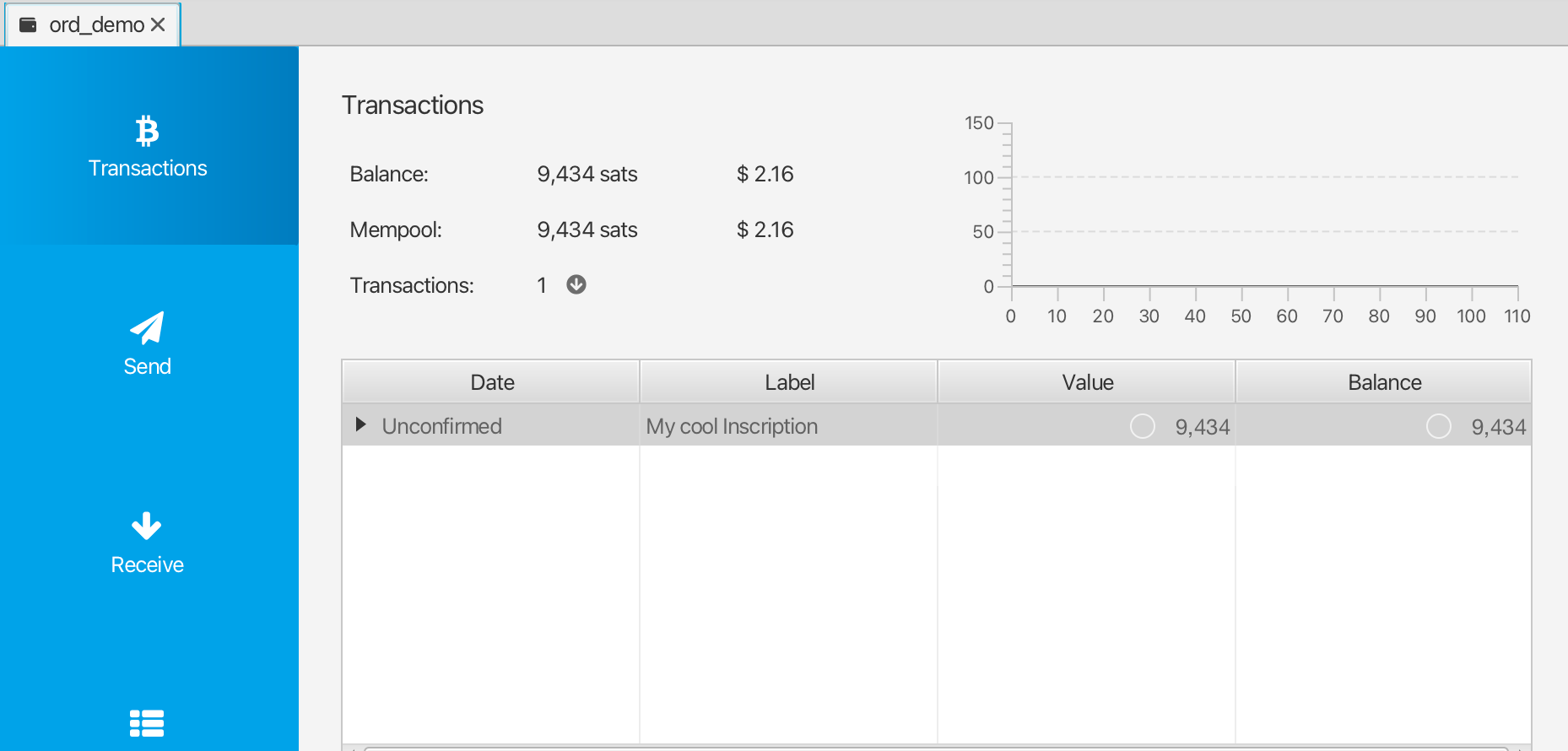

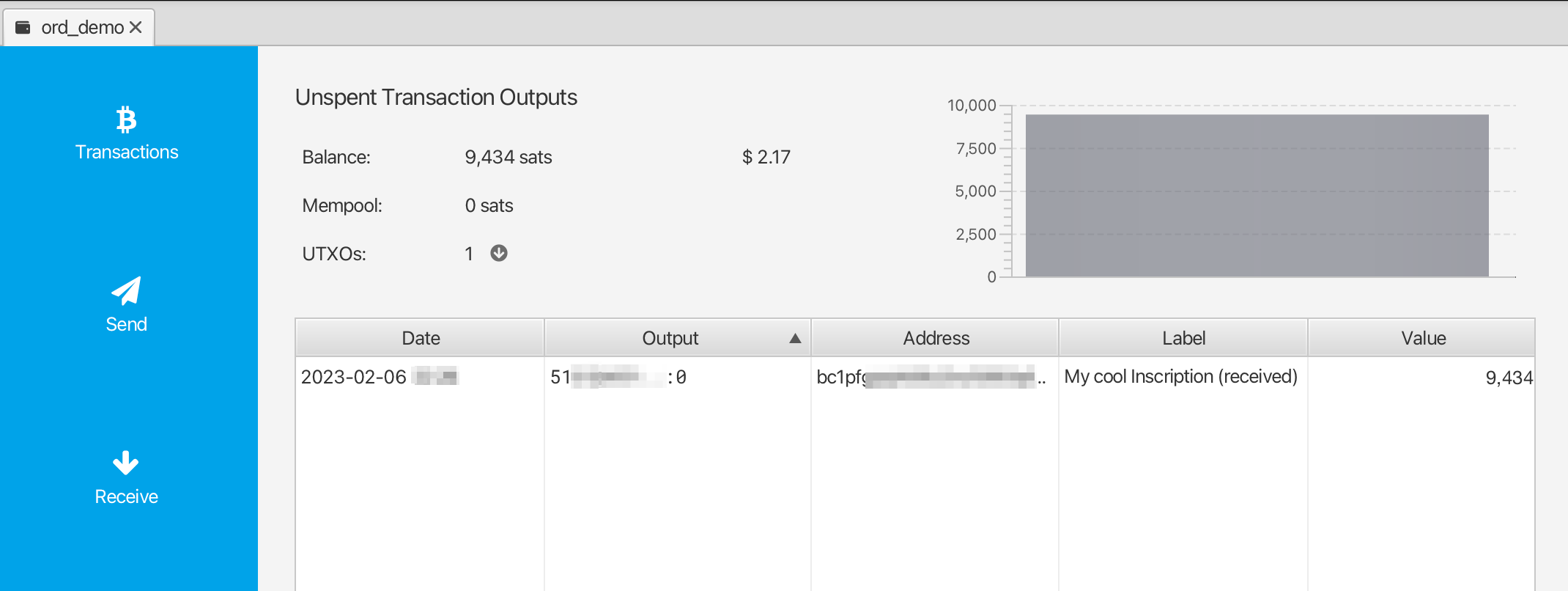

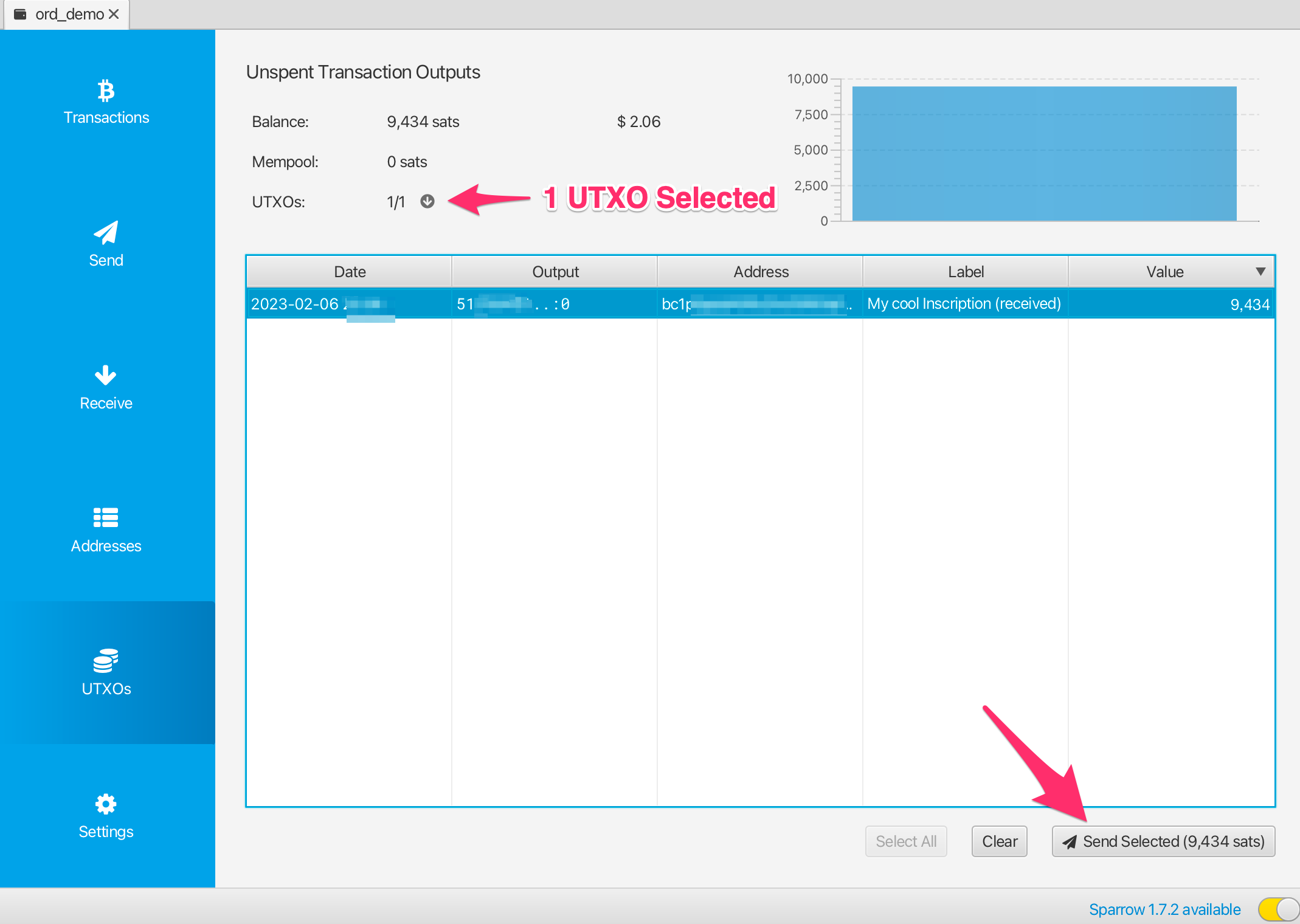

Inscriptions inscribe sats with arbitrary content, creating bitcoin-native digital artifacts, more commonly known as NFTs. Inscriptions do not require a sidechain or separate token.

These inscribed sats can then be transferred using bitcoin transactions, sent to bitcoin addresses, and held in bitcoin UTXOs. These transactions, addresses, and UTXOs are normal bitcoin transactions, addresses, and UTXOS in all respects, with the exception that in order to send individual sats, transactions must control the order and value of inputs and outputs according to ordinal theory.

The inscription content model is that of the web. An inscription consists of a content type, also known as a MIME type, and the content itself, which is a byte string. This allows inscription content to be returned from a web server, and for creating HTML inscriptions that use and remix the content of other inscriptions.

Inscription content is entirely on-chain, stored in taproot script-path spend scripts. Taproot scripts have very few restrictions on their content, and additionally receive the witness discount, making inscription content storage relatively economical.

Since taproot script spends can only be made from existing taproot outputs, inscriptions are made using a two-phase commit/reveal procedure. First, in the commit transaction, a taproot output committing to a script containing the inscription content is created. Second, in the reveal transaction, the output created by the commit transaction is spent, revealing the inscription content on-chain.

Inscription content is serialized using data pushes within unexecuted

conditionals, called "envelopes". Envelopes consist of an OP_FALSE OP_IF … OP_ENDIF wrapping any number of data pushes. Because envelopes are effectively

no-ops, they do not change the semantics of the script in which they are

included, and can be combined with any other locking script.

A text inscription containing the string "Hello, world!" is serialized as follows:

OP_FALSE

OP_IF

OP_PUSH "ord"

OP_PUSH 1

OP_PUSH "text/plain;charset=utf-8"

OP_PUSH 0

OP_PUSH "Hello, world!"

OP_ENDIF

First the string ord is pushed, to disambiguate inscriptions from other uses

of envelopes.

OP_PUSH 1 indicates that the next push contains the content type, and

OP_PUSH 0indicates that subsequent data pushes contain the content itself.

Multiple data pushes must be used for large inscriptions, as one of taproot's

few restrictions is that individual data pushes may not be larger than 520

bytes.

The inscription content is contained within the input of a reveal transaction, and the inscription is made on the first sat of its input if it has no pointer field. This sat can then be tracked using the familiar rules of ordinal theory, allowing it to be transferred, bought, sold, lost to fees, and recovered.

Content

The data model of inscriptions is that of a HTTP response, allowing inscription content to be served by a web server and viewed in a web browser.

Fields

Inscriptions may include fields before an optional body. Each field consists of two data pushes, a tag and a value.

Currently, there are six defined fields:

content_type, with a tag of1, whose value is the MIME type of the body.pointer, with a tag of2, see pointer docs.parent, with a tag of3, see provenance.metadata, with a tag of5, see metadata.metaprotocol, with a tag of7, whose value is the metaprotocol identifier.content_encoding, with a tag of9, whose value is the encoding of the body.delegate, with a tag of11, see delegate.

The beginning of the body and end of fields is indicated with an empty data push.

Unrecognized tags are interpreted differently depending on whether they are even or odd, following the "it's okay to be odd" rule used by the Lightning Network.

Even tags are used for fields which may affect creation, initial assignment, or transfer of an inscription. Thus, inscriptions with unrecognized even fields must be displayed as "unbound", that is, without a location.

Odd tags are used for fields which do not affect creation, initial assignment, or transfer, such as additional metadata, and thus are safe to ignore.

Inscription IDs

The inscriptions are contained within the inputs of a reveal transaction. In order to uniquely identify them they are assigned an ID of the form:

521f8eccffa4c41a3a7728dd012ea5a4a02feed81f41159231251ecf1e5c79dai0

The part in front of the i is the transaction ID (txid) of the reveal

transaction. The number after the i defines the index (starting at 0) of new inscriptions

being inscribed in the reveal transaction.

Inscriptions can either be located in different inputs, within the same input or

a combination of both. In any case the ordering is clear, since a parser would

go through the inputs consecutively and look for all inscription envelopes.

| Input | Inscription Count | Indices |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2 | i0, i1 |

| 1 | 1 | i2 |

| 2 | 3 | i3, i4, i5 |

| 3 | 0 | |

| 4 | 1 | i6 |

Inscription Numbers

Inscriptions are assigned inscription numbers starting at zero, first by the order reveal transactions appear in blocks, and the order that reveal envelopes appear in those transactions.

Due to a historical bug in ord which cannot be fixed without changing a great

many inscription numbers, inscriptions which are revealed and then immediately

spent to fees are numbered as if they appear last in the block in which they

are revealed.

Inscriptions which are cursed are numbered starting at negative one, counting down. Cursed inscriptions on and after the jubilee at block 824544 are vindicated, and are assigned positive inscription numbers.

Sandboxing

HTML and SVG inscriptions are sandboxed in order to prevent references to off-chain content, thus keeping inscriptions immutable and self-contained.

This is accomplished by loading HTML and SVG inscriptions inside iframes with

the sandbox attribute, as well as serving inscription content with

Content-Security-Policy headers.

Self-Reference

The content of the inscription with ID INSCRIPTION_ID must served from the

URL path /content/<INSCRIPTION_ID>.

This allows inscriptions to retrieve their own inscription ID with:

let inscription_id = window.location.pathname.split("/").pop();

If an inscription with ID X delegates to an inscription with ID Y, that is to

say, if inscription X contains a delegate field with value Y, the content of

inscription X must be served from the URL path /content/X, not

/content/Y.

This allows delegating inscriptions to use their own inscription ID as a seed for generative delegate content.

Reinscriptions

Previously inscribed sats can be reinscribed with the --reinscribe command if

the inscription is present in the wallet. This will only append an inscription to

a sat, not change the initial inscription.

Reinscribe with satpoint:

ord wallet inscribe --fee-rate <FEE_RATE> --reinscribe --file <FILE> --satpoint <SATPOINT>

Reinscribe on a sat (requires sat index):

ord --index-sats wallet inscribe --fee-rate <FEE_RATE> --reinscribe --file <FILE> --sat <SAT>

Delegate

Inscriptions may nominate a delegate inscription. Requests for the content of an inscription with a delegate will instead return the content, content type and content encoding of the delegate. This can be used to cheaply create copies of an inscription.

Specification

To create an inscription I with delegate inscription D:

- Create an inscription D. Note that inscription D does not have to exist when making inscription I. It may be inscribed later. Before inscription D is inscribed, requests for the content of inscription I will return a 404.

- Include tag

11, i.e.OP_PUSH 11, in I, with the value of the serialized binary inscription ID of D, serialized as the 32-byteTXID, followed by the four-byte little-endianINDEX, with trailing zeroes omitted.

NB The bytes of a bitcoin transaction ID are reversed in their text representation, so the serialized transaction ID will be in the opposite order.

Example

An example of an inscription which delegates to

000102030405060708090a0b0c0d0e0f101112131415161718191a1b1c1d1e1fi0:

OP_FALSE

OP_IF

OP_PUSH "ord"

OP_PUSH 11

OP_PUSH 0x1f1e1d1c1b1a191817161514131211100f0e0d0c0b0a09080706050403020100

OP_ENDIF

Note that the value of tag 11 is decimal, not hex.

The delegate field value uses the same encoding as the parent field. See provenance for more examples of inscription ID encodings

See examples for on-chain examples of inscriptions that feature this functionality.

Metadata

Inscriptions may include CBOR metadata, stored as data

pushes in fields with tag 5. Since data pushes are limited to 520 bytes,

metadata longer than 520 bytes must be split into multiple tag 5 fields,

which will then be concatenated before decoding.

Metadata is human readable, and all metadata will be displayed to the user with its inscription. Inscribers are encouraged to consider how metadata will be displayed, and make metadata concise and attractive.

Metadata is rendered to HTML for display as follows:

null,true,false, numbers, floats, and strings are rendered as plain text.- Byte strings are rendered as uppercase hexadecimal.

- Arrays are rendered as

<ul>tags, with every element wrapped in<li>tags. - Maps are rendered as

<dl>tags, with every key wrapped in<dt>tags, and every value wrapped in<dd>tags. - Tags are rendered as the tag , enclosed in a

<sup>tag, followed by the value.

CBOR is a complex spec with many different data types, and multiple ways of

representing the same data. Exotic data types, such as tags, floats, and

bignums, and encoding such as indefinite values, may fail to display correctly

or at all. Contributions to ord to remedy this are welcome.

Example

Since CBOR is not human readable, in these examples it is represented as JSON. Keep in mind that this is only for these examples, and JSON metadata will not be displayed correctly.

The metadata {"foo":"bar","baz":[null,true,false,0]} would be included in an inscription as:

OP_FALSE

OP_IF

...

OP_PUSH 0x05 OP_PUSH '{"foo":"bar","baz":[null,true,false,0]}'

...

OP_ENDIF

And rendered as:

<dl>

...

<dt>metadata</dt>

<dd>

<dl>

<dt>foo</dt>

<dd>bar</dd>

<dt>baz</dt>

<dd>

<ul>

<li>null</li>

<li>true</li>

<li>false</li>

<li>0</li>

</ul>

</dd>

</dl>

</dd>

...

</dl>

Metadata longer than 520 bytes must be split into multiple fields:

OP_FALSE

OP_IF

...

OP_PUSH 0x05 OP_PUSH '{"very":"long","metadata":'

OP_PUSH 0x05 OP_PUSH '"is","finally":"done"}'

...

OP_ENDIF

Which would then be concatenated into

{"very":"long","metadata":"is","finally":"done"}.

See examples for on-chain examples of inscriptions that feature this functionality.

Pointer

In order to make an inscription on a sat other than the first of its input, a

zero-based integer, called the "pointer", can be provided with tag 2, causing

the inscription to be made on the sat at the given position in the outputs. If

the pointer is equal to or greater than the number of total sats in the outputs

of the inscribe transaction, it is ignored, and the inscription is made as

usual. The value of the pointer field is a little endian integer, with trailing

zeroes ignored.

An even tag is used, so that old versions of ord consider the inscription to

be unbound, instead of assigning it, incorrectly, to the first sat.

This can be used to create multiple inscriptions in a single transaction on different sats, when otherwise they would be made on the same sat.

Examples

An inscription with pointer 255:

OP_FALSE

OP_IF

OP_PUSH "ord"

OP_PUSH 1

OP_PUSH "text/plain;charset=utf-8"

OP_PUSH 2

OP_PUSH 0xff

OP_PUSH 0

OP_PUSH "Hello, world!"

OP_ENDIF

An inscription with pointer 256:

OP_FALSE

OP_IF

OP_PUSH "ord"

OP_PUSH 1

OP_PUSH "text/plain;charset=utf-8"

OP_PUSH 2

OP_PUSH 0x0001

OP_PUSH 0

OP_PUSH "Hello, world!"

OP_ENDIF

An inscription with pointer 256, with trailing zeroes, which are ignored:

OP_FALSE

OP_IF

OP_PUSH "ord"

OP_PUSH 1

OP_PUSH "text/plain;charset=utf-8"

OP_PUSH 2

OP_PUSH 0x000100

OP_PUSH 0

OP_PUSH "Hello, world!"

OP_ENDIF

Provenance

The owner of an inscription can create child inscriptions, trustlessly establishing the provenance of those children on-chain as having been created by the owner of the parent inscription. This can be used for collections, with the children of a parent inscription being members of the same collection.

Children can themselves have children, allowing for complex hierarchies. For example, an artist might create an inscription representing themselves, with sub inscriptions representing collections that they create, with the children of those sub inscriptions being items in those collections.

Specification

To create a child inscription C with parent inscription P:

- Create an inscribe transaction T as usual for C.

- Spend the parent P in one of the inputs of T.

- Include tag

3, i.e.OP_PUSH 3, in C, with the value of the serialized binary inscription ID of P, serialized as the 32-byteTXID, followed by the four-byte little-endianINDEX, with trailing zeroes omitted.

NB The bytes of a bitcoin transaction ID are reversed in their text representation, so the serialized transaction ID will be in the opposite order.

Example

An example of a child inscription of

000102030405060708090a0b0c0d0e0f101112131415161718191a1b1c1d1e1fi0:

OP_FALSE

OP_IF

OP_PUSH "ord"

OP_PUSH 1

OP_PUSH "text/plain;charset=utf-8"

OP_PUSH 3

OP_PUSH 0x1f1e1d1c1b1a191817161514131211100f0e0d0c0b0a09080706050403020100

OP_PUSH 0

OP_PUSH "Hello, world!"

OP_ENDIF

Note that the value of tag 3 is binary, not hex, and that for the child

inscription to be recognized as a child,

000102030405060708090a0b0c0d0e0f101112131415161718191a1b1c1d1e1fi0 must be

spent as one of the inputs of the inscribe transaction.

Example encoding of inscription ID

000102030405060708090a0b0c0d0e0f101112131415161718191a1b1c1d1e1fi255:

OP_FALSE

OP_IF

…

OP_PUSH 3

OP_PUSH 0x1f1e1d1c1b1a191817161514131211100f0e0d0c0b0a09080706050403020100ff

…

OP_ENDIF

And of inscription ID 000102030405060708090a0b0c0d0e0f101112131415161718191a1b1c1d1e1fi256:

OP_FALSE

OP_IF

…

OP_PUSH 3

OP_PUSH 0x1f1e1d1c1b1a191817161514131211100f0e0d0c0b0a090807060504030201000001

…

OP_ENDIF

Notes

The tag 3 is used because it is the first available odd tag. Unrecognized odd

tags do not make an inscription unbound, so child inscriptions would be

recognized and tracked by old versions of ord.

A collection can be closed by burning the collection's parent inscription, which guarantees that no more items in the collection can be issued.

See examples for on-chain examples of inscriptions that feature this functionality.

Recursion

An important exception to sandboxing is recursion. Recursive endpoints are whitelisted endpoints that allow access to on-chain data, including the content of other inscriptions.

Since changes to recursive endpoints might break inscriptions that rely on

them, recursive endpoints have backwards-compatibility guarantees not shared by

ord server's other endpoints. In particular:

- Recursive endpoints will not be removed

- Object fields returned by recursive endpoints will not be renamed or change types

However, additional object fields may be added or reordered, so inscriptions must handle additional, unexpected fields, and must not expect fields to be returned in a specific order.

Recursion has a number of interesting use-cases:

-

Remixing the content of existing inscriptions.

-

Publishing snippets of code, images, audio, or stylesheets as shared public resources.

-

Generative art collections where an algorithm is inscribed as JavaScript, and instantiated from multiple inscriptions with unique seeds.

-

Generative profile picture collections where accessories and attributes are inscribed as individual images, or in a shared texture atlas, and then combined, collage-style, in unique combinations in multiple inscriptions.

The recursive endpoints are:

/content/<INSCRIPTION_ID>: the content of the inscription with<INSCRIPTION_ID>/r/blockhash/<HEIGHT>: block hash at given block height./r/blockhash: latest block hash./r/blockheight: latest block height./r/blockinfo/<QUERY>: block info.<QUERY>may be a block height or block hash./r/blocktime: UNIX time stamp of latest block./r/children/<INSCRIPTION_ID>: the first 100 child inscription ids./r/children/<INSCRIPTION_ID>/<PAGE>: the set of 100 child inscription ids on<PAGE>./r/children/<INSCRIPTION_ID>/inscriptions: details of the first 100 child inscriptions./r/children/<INSCRIPTION_ID>/inscriptions/<PAGE>: details of the set of 100 child inscriptions on<PAGE>./r/inscription/<INSCRIPTION_ID>: information about an inscription/r/metadata/<INSCRIPTION_ID>: JSON string containing the hex-encoded CBOR metadata./r/parents/<INSCRIPTION_ID>: the first 100 parent inscription ids./r/parents/<INSCRIPTION_ID>/<PAGE>: the set of 100 parent inscription ids on<PAGE>./r/sat/<SAT_NUMBER>: the first 100 inscription ids on a sat./r/sat/<SAT_NUMBER>/<PAGE>: the set of 100 inscription ids on<PAGE>./r/sat/<SAT_NUMBER>/at/<INDEX>: the inscription id at<INDEX>of all inscriptions on a sat.<INDEX>may be a negative number to index from the back.0being the first and-1being the most recent for example.

Note: <SAT_NUMBER> only allows the actual number of a sat no other sat

notations like degree, percentile or decimal. We may expand to allow those in

the future.

Responses from the above recursive endpoints are JSON. For backwards compatibility additional endpoints are supported, some of which return plain-text responses.

/blockheight: latest block height./blockhash: latest block hash./blockhash/<HEIGHT>: block hash at given block height./blocktime: UNIX time stamp of latest block.

Examples

/r/blockhash/0:

"000000000019d6689c085ae165831e934ff763ae46a2a6c172b3f1b60a8ce26f"

/r/blockheight:

777000

/r/blockinfo/0:

Note: feerate_percentiles are feerates at the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th

percentile in sats/vB.

{

"average_fee": 0,

"average_fee_rate": 0,

"bits": 486604799,

"chainwork": "0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000100010001",

"confirmations": 0,

"difficulty": 0.0,

"hash": "000000000019d6689c085ae165831e934ff763ae46a2a6c172b3f1b60a8ce26f",

"feerate_percentiles": [0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

"height": 0,

"max_fee": 0,

"max_fee_rate": 0,

"max_tx_size": 0,

"median_fee": 0,

"median_time": 1231006505,

"merkle_root": "0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000",

"min_fee": 0,

"min_fee_rate": 0,

"next_block": null,

"nonce": 0,

"previous_block": null,

"subsidy": 5000000000,

"target": "00000000ffff0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000",

"timestamp": 1231006505,

"total_fee": 0,

"total_size": 0,

"total_weight": 0,

"transaction_count": 1,

"version": 1

}

/r/blocktime:

1700770905

/r/children/60bcf821240064a9c55225c4f01711b0ebbcab39aa3fafeefe4299ab158536fai0/49:

{

"ids":[

"7cd66b8e3a63dcd2fada917119830286bca0637267709d6df1ca78d98a1b4487i4900",

"7cd66b8e3a63dcd2fada917119830286bca0637267709d6df1ca78d98a1b4487i4901",

...

"7cd66b8e3a63dcd2fada917119830286bca0637267709d6df1ca78d98a1b4487i4935",

"7cd66b8e3a63dcd2fada917119830286bca0637267709d6df1ca78d98a1b4487i4936"

],

"more":false,

"page":49

}

/r/children/60bcf821240064a9c55225c4f01711b0ebbcab39aa3fafeefe4299ab158536fai0/inscriptions/49:

{

"children": [

{

"charms": [

"cursed"

],

"fee": 44,

"height": 813929,

"id": "7cd66b8e3a63dcd2fada917119830286bca0637267709d6df1ca78d98a1b4487i4900",

"number": -223695,

"output": "dcaaeacf58faea0927468ea5a93f33b7d7447841e66f75db5a655d735510c518:0",

"sat": 1897135510683785,

"satpoint": "dcaaeacf58faea0927468ea5a93f33b7d7447841e66f75db5a655d735510c518:0:74188588",

"timestamp": 1698326262

},

...

{

"charms": [

"cursed"

],

"fee": 44,

"height": 813929,

"id": "7cd66b8e3a63dcd2fada917119830286bca0637267709d6df1ca78d98a1b4487i4936",

"number": -223731,

"output": "dcaaeacf58faea0927468ea5a93f33b7d7447841e66f75db5a655d735510c518:0",

"sat": 1897135510683821,

"satpoint": "dcaaeacf58faea0927468ea5a93f33b7d7447841e66f75db5a655d735510c518:0:74188624",

"timestamp": 1698326262

}

],

"more": false,

"page": 49

}

/r/inscription/3bd72a7ef68776c9429961e43043ff65efa7fb2d8bb407386a9e3b19f149bc36i0

{

"charms": [],

"content_type": "image/png",

"content_length": 144037,

"delegate": null,

"fee": 36352,

"height": 209,

"id": "3bd72a7ef68776c9429961e43043ff65efa7fb2d8bb407386a9e3b19f149bc36i0",

"number": 2,

"output": "3bd72a7ef68776c9429961e43043ff65efa7fb2d8bb407386a9e3b19f149bc36:0",

"sat": null,

"satpoint": "3bd72a7ef68776c9429961e43043ff65efa7fb2d8bb407386a9e3b19f149bc36:0:0",

"timestamp": 1708312562,

"value": 10000,

"address": "bc1pz4kvfpurqc2hwgrq0nwtfve2lfxvdpfcdpzc6ujchyr3ztj6gd9sfr6ayf"

}

/r/metadata/35b66389b44535861c44b2b18ed602997ee11db9a30d384ae89630c9fc6f011fi3:

"a2657469746c65664d656d6f727966617574686f726e79656c6c6f775f6f72645f626f74"

/r/sat/1023795949035695:

{

"ids":[

"17541f6adf6eb160d52bc6eb0a3546c7c1d2adfe607b1a3cddc72cc0619526adi0"

],

"more":false,

"page":0

}

/r/sat/1023795949035695/at/-1:

{

"id":"17541f6adf6eb160d52bc6eb0a3546c7c1d2adfe607b1a3cddc72cc0619526adi0"

}

See examples for on-chain examples of inscriptions that feature this functionality.

Rendering

Aspect Ratio

Inscriptions should be rendered with a square aspect ratio. Non-square aspect ratio inscriptions should not be cropped, and should instead be centered and resized to fit within their container.

Maximum Size

The ord explorer, used by ordinals.com, displays

inscription previews with a maximum size of 576 by 576 pixels, making it a

reasonable choice when choosing a maximum display size.

Image Rendering

The CSS image-rendering property controls how images are resampled when

upscaled and downscaled.

When downscaling image inscriptions, image-rendering: auto, should be used.

This is desirable even when downscaling pixel art.

When upscaling image inscriptions other than AVIF, image-rendering: pixelated

should be used. This is desirable when upscaling pixel art, since it preserves

the sharp edges of pixels. It is undesirable when upscaling non-pixel art, but

should still be used for visual compatibility with the ord explorer.

When upscaling AVIF and JPEG XL inscriptions, image-rendering: auto should be

used. This allows inscribers to opt-in to non-pixelated upscaling for non-pixel

art inscriptions. Until such time as JPEG XL is widely supported by browsers,

it is not a recommended image format.

Inscription Examples

Delegate

- The first delegate inscription.

- The Oscillations * collection utilizes delegation, provenance, recursion, sat endpoint, and detects the kind of sat that each piece is inscribed on (sattribute-aware). Each piece is a delegate of this inscription.

- This inscription was inscribed as a delegate of this inscription and is also the parent inscription of a rune.

Metadata

- Each member in the FUN collection has metadata that describes its attributes.

- This inscription uses its own metadata to draw the ordinal image.

Provenance

- Inscription 0 is the parent inscription for Casey's sugar skull collection, a grandparent for the FUN! collection, and the grandparent for the sleepiest rune.

- With the Rug Me collection, owners are able to change the background color by inscribing a child to it.

- This Bitcoin Magazine Cover renders the children as part of the parent inscription.

- The yellow_ord_bot has many different quotes as cursed children.

- The Spellbound collection from the Wizard of Ord utilizes recursion, delegation, metadata, provenance, postage, location, compression.

Recursion

- Inscription 12992 was the first recursive inscription inscribed on mainnet.

- OnChain Monkey Genesis (BTC) was one of the earliest collections to use recursion to create its PFP art.

- Blob is a recursive generative collection that seeds its generation with metadata and uses threeJS, React 3 Fiber and other libraries recursively.

- The GPU Ordinals collection takes recursive content and transforms it before rendering, creating what is termed as 'super-recursion'. Use Google Chrome and headphones to experience the spatial audio.

- The Abstractii Genesis collection uses the inscriptions ID as a seed to generate its art.

- The Abstractii Evolved generative collection uses the recursive blockheight endpoint as a seed to generate its art.

- This code is called recursively in this inscription to generate music.

- This code is called recursively in this inscription, allowing it to function as a pixel art drawing program.

Runes

Runes allow Bitcoin transactions to etch, mint, and transfer Bitcoin-native digital commodities.

Whereas every inscription is unique, every unit of a rune is the same. They are interchangeable tokens, fit for a variety of purposes.

Runestones

Rune protocol messages, called runestones, are stored in Bitcoin transaction outputs.

A runestone output's script pubkey begins with an OP_RETURN, followed by

OP_13, followed by zero or more data pushes. These data pushes are

concatenated and decoded into a sequence of 128-bit integers, and finally

parsed into a runestone.

A transaction may have at most one runestone.

A runestone may etch a new rune, mint an existing rune, and transfer runes from a transaction's inputs to its outputs.

A transaction output may hold balances of any number of runes.

Runes are identified by IDs, which consist of the block in which a rune was

etched and the index of the etching transaction within that block, represented

in text as BLOCK:TX. For example, the ID of the rune etched in the 20th

transaction of the 500th block is 500:20.

Etching

Runes come into existence by being etched. Etching creates a rune and sets its properties. Once set, these properties are immutable, even to its etcher.

Name

Names consist of the letters A through Z and are between one and twenty-six

letters long. For example UNCOMMONGOODS is a rune name.

Names may contain spacers, represented as bullets, to aid readability.

UNCOMMONGOODS might be etched as UNCOMMON•GOODS.

The uniqueness of a name does not depend on spacers. Thus, a rune may not be etched with the same sequence of letters as an existing rune, even if it has different spacers.

Spacers can only be placed between two letters. Finally, spacers do not count towards the letter count.

Divisibility

A rune's divisibility is how finely it may be divided into its atomic units. Divisibility is expressed as the number of digits permissible after the decimal point in an amount of runes. A rune with divisibility 0 may not be divided. A unit of a rune with divisibility 1 may be divided into ten sub-units, a rune with divisibility 2 may be divided into a hundred, and so on.

Symbol

A rune's currency symbol is a single Unicode code point, for example $, ⧉,

or 🧿, displayed after quantities of that rune.

101 atomic units of a rune with divisibility 2 and symbol 🧿 would be

rendered as 1.01 🧿.

If a rune does not have a symbol, the generic currency sign ¤, also called a

scarab, should be used.

Premine

The etcher of a rune may optionally allocate to themselves units of the rune being etched. This allocation is called a premine.

Terms

A rune may have an open mint, allowing anyone to create and allocate units of that rune for themselves. An open mint is subject to terms, which are set upon etching.

A mint is open while all terms of the mint are satisfied, and closed when any of them are not. For example, a mint may be limited to a starting height, an ending height, and a cap, and will be open between the starting height and ending height, or until the cap is reached, whichever comes first.

Cap

The number of times a rune may be minted is its cap. A mint is closed once the cap is reached.

Amount

Each mint transaction creates a fixed amount of new units of a rune.

Start Height

A mint is open starting in the block with the given start height.

End Height

A rune may not be minted in or after the block with the given end height.

Start Offset

A mint is open starting in the block whose height is equal to the start offset plus the height of the block in which the rune was etched.

End Offset

A rune may not be minted in or after the block whose height is equal to the end offset plus the height of the block in which the rune was etched.

Minting

While a rune's mint is open, anyone may create a mint transaction that creates a fixed amount of new units of that rune, subject to the terms of the mint.

Transferring

When transaction inputs contain runes, or new runes are created by a premine or mint, those runes are transferred to that transaction's outputs. A transaction's runestone may change how input runes transfer to outputs.

Edicts

A runestone may contain any number of edicts. Edicts consist of a rune ID, an amount, and an output number. Edicts are processed in order, allocating unallocated runes to outputs.

Pointer

After all edicts are processed, remaining unallocated runes are transferred to

the transaction's first non-OP_RETURN output. A runestone may optionally

contain a pointer that specifies an alternative default output.

Burning

Runes may be burned by transferring them to an OP_RETURN output with an edict

or pointer.

Cenotaphs

Runestones may be malformed for a number of reasons, including non-pushdata

opcodes in the runestone OP_RETURN, invalid varints, or unrecognized

runestone fields.

Malformed runestones are termed cenotaphs.

Runes input to a transaction with a cenotaph are burned. Runes etched in a transaction with a cenotaph are set as unmintable. Mints in a transaction with a cenotaph count towards the mint cap, but the minted runes are burned.

Cenotaphs are an upgrade mechanism, allowing runestones to be given new semantics that change how runes are created and transferred, while not misleading unupgraded clients as to the location of those runes, as unupgraded clients will see those runes as having been burned.

Runes Does Not Have a Specification

The Runes reference implementation, ord, is the normative specification of

the Runes protocol.

Nothing you read here or elsewhere, aside from the code of ord, is a

specification. This prose description of the runes protocol is provided as a

guide to the behavior of ord, and the code of ord itself should always be

consulted to confirm the correctness of any prose description.

If, due to a bug in ord, this document diverges from the actual behavior of

ord and it is impractically disruptive to change ord's behavior, this

document will be amended to agree with ord's actual behavior.

Users of alternative implementations do so at their own risk, and services

wishing to integrate Runes are strongly encouraged to use ord itself to make

Runes transactions, and to determine the state of runes, mints, and balances.

Runestones

Rune protocol messages are termed "runestones".

The Runes protocol activates on block 840,000. Runestones in earlier blocks are ignored.

Abstractly, runestones contain the following fields:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct Runestone { edicts: Vec<Edict>, etching: Option<Etching>, mint: Option<RuneId>, pointer: Option<u32>, } }

Runes are created by etchings:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct Etching { divisibility: Option<u8>, premine: Option<u128>, rune: Option<Rune>, spacers: Option<u32>, symbol: Option<char>, terms: Option<Terms>, } }

Which may contain mint terms:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct Terms { amount: Option<u128>, cap: Option<u128>, height: (Option<u64>, Option<u64>), offset: (Option<u64>, Option<u64>), } }

Runes are transferred by edict:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct Edict { id: RuneId, amount: u128, output: u32, } }

Rune IDs are encoded as the block height and transaction index of the transaction in which the rune was etched:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct RuneId { block: u64, tx: u32, } }

Rune IDs are represented in text as BLOCK:TX.

Rune names are encoded as modified base-26 integers:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct Rune(u128); }

Deciphering

Runestones are deciphered from transactions with the following steps:

-

Find the first transaction output whose script pubkey begins with

OP_RETURN OP_13. -

Concatenate all following data pushes into a payload buffer.

-

Decode a sequence 128-bit LEB128 integers from the payload buffer.

-

Parse the sequence of integers into an untyped message.

-

Parse the untyped message into a runestone.

Deciphering may produce a malformed runestone, termed a cenotaph.

Locating the Runestone Output

Outputs are searched for the first script pubkey that beings with OP_RETURN OP_13. If deciphering fails, later matching outputs are not considered.

Assembling the Payload Buffer

The payload buffer is assembled by concatenating data pushes, after OP_13, in

the matching script pubkey.

Data pushes are opcodes 0 through 78 inclusive. If a non-data push opcode is encountered, i.e., any opcode equal to or greater than opcode 79, the deciphered runestone is a cenotaph with no etching, mint, or edicts.

Decoding the Integer Sequence

A sequence of 128-bit integers are decoded from the payload as LEB128 varints.

LEB128 varints are encoded as sequence of bytes, each of which has the most-significant bit set, except for the last.

If a LEB128 varint contains more than 18 bytes, would overflow a u128, or is truncated, meaning that the end of the payload buffer is reached before encountering a byte with the continuation bit not set, the decoded runestone is a cenotaph with no etching, mint, or edicts.

Parsing the Message

The integer sequence is parsed into an untyped message:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct Message { fields: Map<u128, Vec<u128>>, edicts: Vec<Edict>, } }

The integers are interpreted as a sequence of tag/value pairs, with duplicate tags appending their value to the field value.

If a tag with value zero is encountered, all following integers are interpreted as a series of four-integer edicts, each consisting of a rune ID block height, rune ID transaction index, amount, and output.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct Edict { id: RuneId, amount: u128, output: u32, } }

Rune ID block heights and transaction indices in edicts are delta encoded.

Edict rune ID decoding starts with a base block height and transaction index of zero. When decoding each rune ID, first the encoded block height delta is added to the base block height. If the block height delta is zero, the next integer is a transaction index delta. If the block height delta is greater than zero, the next integer is instead an absolute transaction index.

This implies that edicts must first be sorted by rune ID before being encoded in a runestone.

For example, to encode the following edicts:

| block | TX | amount | output |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 5 | 5 | 1 |

| 50 | 1 | 25 | 4 |

| 10 | 7 | 1 | 8 |

| 10 | 5 | 10 | 3 |

They are first sorted by block height and transaction index:

| block | TX | amount | output |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 5 | 5 | 1 |

| 10 | 5 | 10 | 3 |

| 10 | 7 | 1 | 8 |

| 50 | 1 | 25 | 4 |

And then delta encoded as:

| block delta | TX delta | amount | output |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 5 | 5 | 1 |

| 0 | 0 | 10 | 3 |

| 0 | 2 | 1 | 8 |

| 40 | 1 | 25 | 4 |

If an edict output is greater than the number of outputs of the transaction, an edict rune ID is encountered with block zero and nonzero transaction index, or a field is truncated, meaning a tag is encountered without a value, the decoded runestone is a cenotaph.

Note that if a cenotaph is produced here, the cenotaph is not empty, meaning that it contains the fields and edicts, which may include an etching and mint.

Parsing the Runestone

The runestone:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct Runestone { edicts: Vec<Edict>, etching: Option<Etching>, mint: Option<RuneId>, pointer: Option<u32>, } }

Is parsed from the unsigned message using the following tags:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { enum Tag { Body = 0, Flags = 2, Rune = 4, Premine = 6, Cap = 8, Amount = 10, HeightStart = 12, HeightEnd = 14, OffsetStart = 16, OffsetEnd = 18, Mint = 20, Pointer = 22, Cenotaph = 126, Divisibility = 1, Spacers = 3, Symbol = 5, Nop = 127, } }

Note that tags are grouped by parity, i.e., whether they are even or odd. Unrecognized odd tags are ignored. Unrecognized even tags produce a cenotaph.

All unused tags are reserved for use by the protocol, may be assigned at any time, and should not be used.

Body

The Body tag marks the end of the runestone's fields, causing all following

integers to be interpreted as edicts.

Flags

The Flag field contains a bitmap of flags, whose position is 1 << FLAG_VALUE:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { enum Flag { Etching = 0, Terms = 1, Turbo = 2, Cenotaph = 127, } }

The Etching flag marks this transaction as containing an etching.

The Terms flag marks this transaction's etching as having open mint terms.

The Turbo flag marks this transaction's etching as opting into future

protocol changes. These protocol changes may increase light client validation

costs, or just be highly degenerate.

The Cenotaph flag is unrecognized.

If the value of the flags field after removing recognized flags is nonzero, the runestone is a cenotaph.

Rune

The Rune field contains the name of the rune being etched. If the Etching

flag is set but the Rune field is omitted, a reserved rune name is

allocated.

Premine

The Premine field contains the amount of premined runes.

Cap

The Cap field contains the allowed number of mints.

Amount

The Amount field contains the amount of runes each mint transaction receives.

HeightStart and HeightEnd

The HeightStart and HeightEnd fields contain the mint's starting and ending

absolute block heights, respectively. The mint is open starting in the block

with height HeightStart, and closes in the block with height HeightEnd.

OffsetStart and OffsetEnd

The OffsetStart and OffsetEnd fields contain the mint's starting and ending

block heights, relative to the block in which the etching is mined. The mint is

open starting in the block with height OffsetStart + ETCHING_HEIGHT, and

closes in the block with height OffsetEnd + ETCHING_HEIGHT.

Mint

The Mint field contains the Rune ID of the rune to be minted in this

transaction.

Pointer

The Pointer field contains the index of the output to which runes unallocated

by edicts should be transferred. If the Pointer field is absent, unallocated

runes are transferred to the first non-OP_RETURN output. If the pointer is

greater than the number of outputs, the runestone is a cenotaph.

Cenotaph

The Cenotaph field is unrecognized.

Divisibility

The Divisibility field, raised to the power of ten, is the number of subunits

in a super unit of runes.

For example, the amount 1234 of different runes with divisibility 0 through 3

is displayed as follows:

| Divisibility | Display |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1234 |

| 1 | 123.4 |

| 2 | 12.34 |

| 3 | 1.234 |

Spacers

The Spacers field is a bitfield of • spacers that should be displayed

between the letters of the rune's name.

The Nth field of the bitfield, starting from the least significant, determines whether or not a spacer should be displayed between the Nth and N+1th character, starting from the left of the rune's name.

For example, the rune name AAAA rendered with different spacers:

| Spacers | Display |

|---|---|

| 0b1 | A•AAA |

| 0b11 | A•A•AA |

| 0b10 | AA•AA |

| 0b111 | A•A•A•A |

Trailing spacers are ignored.

Symbol

The Symbol field is the Unicode codepoint of the Rune's currency symbol,

which should be displayed after amounts of that rune. If a rune does not have a

currency symbol, the generic currency character ¤ should be used.

For example, if the Symbol is # and the divisibility is 2, the amount of

1234 units should be displayed as 12.34 #.

Nop

The Nop field is unrecognized.

Cenotaphs

Cenotaphs have the following effects:

-

All runes input to a transaction containing a cenotaph are burned.

-

If the runestone that produced the cenotaph contained an etching, the etched rune has supply zero and is unmintable.

-

If the runestone that produced the cenotaph is a mint, the mint counts against the mint cap and the minted runes are burned.

Cenotaphs may be created if a runestone contains an unrecognized even tag, an unrecognized flag, an edict with an output number greater than the number of inputs, a rune ID with block zero and nonzero transaction index, a malformed varint, a non-datapush instruction in the runestone output script pubkey, a tag without a following value, or trailing integers not part of an edict.

Executing the Runestone

Runestones are executed in the order their transactions are included in blocks.

Etchings

A runestone may contain an etching:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct Etching { divisibility: Option<u8>, premine: Option<u128>, rune: Option<Rune>, spacers: Option<u32>, symbol: Option<char>, terms: Option<Terms>, } }

rune is the name of the rune to be etched, encoded as modified base-26

integer.

Rune names consist of the letters A through Z, with the following encoding:

| Name | Encoding |

|---|---|

| A | 0 |

| B | 1 |

| … | … |

| Y | 24 |

| Z | 25 |

| AA | 26 |

| AB | 27 |

| … | … |

| AY | 50 |

| AZ | 51 |

| BA | 52 |

And so on and so on.

Rune names AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA and above are reserved.

If rune is omitted a reserved rune name is allocated as follows:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn reserve(block: u64, tx: u32) -> Rune { Rune( 6402364363415443603228541259936211926 + (u128::from(block) << 32 | u128::from(tx)) ) } }

6402364363415443603228541259936211926 corresponds to the rune name

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA.

If rune is present, it must be unlocked as of the block in which the etching

appears.

Initially, all rune names of length thirteen and longer, up until the first reserved rune name, are unlocked.

Runes begin unlocking in block 840,000, the block in which the runes protocol activates.

Thereafter, every 17,500 block period, the next shortest length of rune names

is continuously unlocked. So, between block 840,000 and block 857,500, the

twelve-character rune names are unlocked, between block 857,500 and block

875,000 the eleven character rune names are unlocked, and so on and so on,

until the one-character rune names are unlocked between block 1,032,500 and

block 1,050,000. See the ord codebase for the precise unlocking schedule.

To prevent front running an etching that has been broadcast but not mined, if a non-reserved rune name is being etched, the etching transaction must contain a valid commitment to the name being etched.

A commitment consists of a data push of the rune name, encoded as a little-endian integer with trailing zero bytes elided, present in an input witness tapscript where the output being spent has at least six confirmations.

If a valid commitment is not present, the etching is ignored.

Minting

A runestone may mint a rune by including the rune's ID in the Mint field.

If the mint is open, the mint amount is added to the unallocated runes in the

transaction's inputs. These runes may be transferred using edicts, and will

otherwise be transferred to the first non-OP_RETURN output, or the output

designated by the Pointer field.

Mints may be made in any transaction after an etching, including in the same block.

Transferring

Runes are transferred by edict:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct Edict { id: RuneId, amount: u128, output: u32, } }

A runestone may contain any number of edicts, which are processed in sequence.

Before edicts are processed, input runes, as well as minted or premined runes, if any, are unallocated.

Each edict decrements the unallocated balance of rune id and increments the

balance allocated to transaction outputs of rune id.

If an edict would allocate more runes than are currently unallocated, the

amount is reduced to the number of currently unallocated runes. In other

words, the edict allocates all remaining unallocated units of rune id.

Because the ID of an etched rune is not known before it is included in a block,

ID 0:0 is used to mean the rune being etched in this transaction, if any.

An edict with amount zero allocates all remaining units of rune id.

An edict with output equal to the number of transaction outputs allocates

amount runes to each non-OP_RETURN output in order.

An edict with amount zero and output equal to the number of transaction

outputs divides all unallocated units of rune id between each non-OP_RETURN

output. If the number of unallocated runes is not divisible by the number of

non-OP_RETURN outputs, 1 additional rune is assigned to the first R

non-OP_RETURN outputs, where R is the remainder after dividing the balance

of unallocated units of rune id by the number of non-OP_RETURN outputs.

If any edict in a runestone has a rune ID with block zero and tx greater

than zero, or output greater than the number of transaction outputs, the

runestone is a cenotaph.

Note that edicts in cenotaphs are not processed, and all input runes are burned.

Ordinal Theory FAQ

What is ordinal theory?

Ordinal theory is a protocol for assigning serial numbers to satoshis, the smallest subdivision of a bitcoin, and tracking those satoshis as they are spent by transactions.

These serial numbers are large numbers, like this 804766073970493. Every satoshi, which is ¹⁄₁₀₀₀₀₀₀₀₀ of a bitcoin, has an ordinal number.

Does ordinal theory require a side chain, a separate token, or changes to Bitcoin?

Nope! Ordinal theory works right now, without a side chain, and the only token needed is bitcoin itself.

What is ordinal theory good for?

Collecting, trading, and scheming. Ordinal theory assigns identities to individual satoshis, allowing them to be individually tracked and traded, as curios and for numismatic value.

Ordinal theory also enables inscriptions, a protocol for attaching arbitrary content to individual satoshis, turning them into bitcoin-native digital artifacts.

How does ordinal theory work?

Ordinal numbers are assigned to satoshis in the order in which they are mined. The first satoshi in the first block has ordinal number 0, the second has ordinal number 1, and the last satoshi of the first block has ordinal number 4,999,999,999.

Satoshis live in outputs, but transactions destroy outputs and create new ones, so ordinal theory uses an algorithm to determine how satoshis hop from the inputs of a transaction to its outputs.

Fortunately, that algorithm is very simple.

Satoshis transfer in first-in-first-out order. Think of the inputs to a transaction as being a list of satoshis, and the outputs as a list of slots, waiting to receive a satoshi. To assign input satoshis to slots, go through each satoshi in the inputs in order, and assign each to the first available slot in the outputs.

Let's imagine a transaction with three inputs and two outputs. The inputs are on the left of the arrow and the outputs are on the right, all labeled with their values:

[2] [1] [3] → [4] [2]

Now let's label the same transaction with the ordinal numbers of the satoshis that each input contains, and question marks for each output slot. Ordinal numbers are large, so let's use letters to represent them:

[a b] [c] [d e f] → [? ? ? ?] [? ?]

To figure out which satoshi goes to which output, go through the input satoshis in order and assign each to a question mark:

[a b] [c] [d e f] → [a b c d] [e f]

What about fees, you might ask? Good question! Let's imagine the same transaction, this time with a two satoshi fee. Transactions with fees send more satoshis in the inputs than are received by the outputs, so to make our transaction into one that pays fees, we'll remove the second output:

[2] [1] [3] → [4]

The satoshis e and f now have nowhere to go in the outputs:

[a b] [c] [d e f] → [a b c d]

So they go to the miner who mined the block as fees. The BIP has the details, but in short, fees paid by transactions are treated as extra inputs to the coinbase transaction, and are ordered how their corresponding transactions are ordered in the block. The coinbase transaction of the block might look like this:

[SUBSIDY] [e f] → [SUBSIDY e f]

Where can I find the nitty-gritty details?

Why are sat inscriptions called "digital artifacts" instead of "NFTs"?

An inscription is an NFT, but the term "digital artifact" is used instead, because it's simple, suggestive, and familiar.

The phrase "digital artifact" is highly suggestive, even to someone who has never heard the term before. In comparison, NFT is an acronym, and doesn't provide any indication of what it means if you haven't heard the term before.

Additionally, "NFT" feels like financial terminology, and the both word "fungible" and sense of the word "token" as used in "NFT" is uncommon outside of financial contexts.

How do sat inscriptions compare to…

Ethereum NFTs?

Inscriptions are always immutable.

There is simply no way to for the creator of an inscription, or the owner of an inscription, to modify it after it has been created.

Ethereum NFTs can be immutable, but many are not, and can be changed or deleted by the NFT contract owner.

In order to make sure that a particular Ethereum NFT is immutable, the contract code must be audited, which requires detailed knowledge of the EVM and Solidity semantics.

It is very hard for a non-technical user to determine whether or not a given Ethereum NFT is mutable or immutable, and Ethereum NFT platforms make no effort to distinguish whether an NFT is mutable or immutable, and whether the contract source code is available and has been audited.

Inscription content is always on-chain.

There is no way for an inscription to refer to off-chain content. This makes inscriptions more durable, because content cannot be lost, and scarcer, because inscription creators must pay fees proportional to the size of the content.

Some Ethereum NFT content is on-chain, but much is off-chain, and is stored on platforms like IPFS or Arweave, or on traditional, fully centralized web servers. Content on IPFS is not guaranteed to continue to be available, and some NFT content stored on IPFS has already been lost. Platforms like Arweave rely on weak economic assumptions, and will likely fail catastrophically when these economic assumptions are no longer met. Centralized web servers may disappear at any time.

It is very hard for a non-technical user to determine where the content of a given Ethereum NFT is stored.

Inscriptions are much simpler.

Ethereum NFTs depend on the Ethereum network and virtual machine, which are highly complex, constantly changing, and which introduce changes via backwards-incompatible hard forks.

Inscriptions, on the other hand, depend on the Bitcoin blockchain, which is relatively simple and conservative, and which introduces changes via backwards-compatible soft forks.

Inscriptions are more secure.

Inscriptions inherit Bitcoin's transaction model, which allow a user to see exactly which inscriptions are being transferred by a transaction before they sign it. Inscriptions can be offered for sale using partially signed transactions, which don't require allowing a third party, such as an exchange or marketplace, to transfer them on the user's behalf.

By comparison, Ethereum NFTs are plagued with end-user security vulnerabilities. It is commonplace to blind-sign transactions, grant third-party apps unlimited permissions over a user's NFTs, and interact with complex and unpredictable smart contracts. This creates a minefield of hazards for Ethereum NFT users which are simply not a concern for ordinal theorists.

Inscriptions are scarcer.

Inscriptions require bitcoin to mint, transfer, and store. This seems like a downside on the surface, but the raison d'etre of digital artifacts is to be scarce and thus valuable.

Ethereum NFTs, on the other hand, can be minted in virtually unlimited qualities with a single transaction, making them inherently less scarce, and thus, potentially less valuable.

Inscriptions do not pretend to support on-chain royalties.

On-chain royalties are a good idea in theory but not in practice. Royalty payment cannot be enforced on-chain without complex and invasive restrictions. The Ethereum NFT ecosystem is currently grappling with confusion around royalties, and is collectively coming to grips with the reality that on-chain royalties, which were messaged to artists as an advantage of NFTs, are not possible, while platforms race to the bottom and remove royalty support.

Inscriptions avoid this situation entirely by making no false promises of supporting royalties on-chain, thus avoiding the confusion, chaos, and negativity of the Ethereum NFT situation.

Inscriptions unlock new markets.

Bitcoin's market capitalization and liquidity are greater than Ethereum's by a large margin. Much of this liquidity is not available to Ethereum NFTs, since many Bitcoiners prefer not to interact with the Ethereum ecosystem due to concerns related to simplicity, security, and decentralization.

Such Bitcoiners may be more interested in inscriptions than Ethereum NFTs, unlocking new classes of collector.

Inscriptions have a richer data model.

Inscriptions consist of a content type, also known as a MIME type, and content, which is an arbitrary byte string. This is the same data model used by the web, and allows inscription content to evolve with the web, and come to support any kind of content supported by web browsers, without requiring changes to the underlying protocol.

RGB and Taro assets?

RGB and Taro are both second-layer asset protocols built on Bitcoin. Compared to inscriptions, they are much more complicated, but much more featureful.

Ordinal theory has been designed from the ground up for digital artifacts, whereas the primary use-case of RGB and Taro are fungible tokens, so the user experience for inscriptions is likely to be simpler and more polished than the user experience for RGB and Taro NFTs.

RGB and Taro both store content off-chain, which requires additional infrastructure, and which may be lost. By contrast, inscription content is stored on-chain, and cannot be lost.

Ordinal theory, RGB, and Taro are all very early, so this is speculation, but ordinal theory's focus may give it the edge in terms of features for digital artifacts, including a better content model, and features like globally unique symbols.

Counterparty assets?

Counterparty has its own token, XCP, which is required for some functionality, which makes most bitcoiners regard it as an altcoin, and not an extension or second layer for bitcoin.

Ordinal theory has been designed from the ground up for digital artifacts, whereas Counterparty was primarily designed for financial token issuance.

Inscriptions for…

Artists

Inscriptions are on Bitcoin. Bitcoin is the digital currency with the highest status and greatest chance of long-term survival. If you want to guarantee that your art survives into the future, there is no better way to publish it than as inscriptions.

Cheaper on-chain storage. At $20,000 per BTC and the minimum relay fee of 1 satoshi per vbyte, publishing inscription content costs $50 per 1 million bytes.

Inscriptions are early! Inscriptions are still in development, and have not yet launched on mainnet. This gives you an opportunity to be an early adopter, and explore the medium as it evolves.

Inscriptions are simple. Inscriptions do not require writing or understanding smart contracts.

Inscriptions unlock new liquidity. Inscriptions are more accessible and appealing to bitcoin holders, unlocking an entirely new class of collector.

Inscriptions are designed for digital artifacts. Inscriptions are designed from the ground up to support NFTs, and feature a better data model, and features like globally unique symbols and enhanced provenance.

Inscriptions do not support on-chain royalties. This is negative, but only depending on how you look at it. On-chain royalties have been a boon for creators, but have also created a huge amount of confusion in the Ethereum NFT ecosystem. The ecosystem now grapples with this issue, and is engaged in a race to the bottom, towards a royalties-optional future. Inscriptions have no support for on-chain royalties, because they are technically infeasible. If you choose to create inscriptions, there are many ways you can work around this limitation: withhold a portion of your inscriptions for future sale, to benefit from future appreciation, or perhaps offer perks for users who respect optional royalties.

Collectors

Inscriptions are simple, clear, and have no surprises. They are always immutable and on-chain, with no special due diligence required.

Inscriptions are on Bitcoin. You can verify the location and properties of inscriptions easily with Bitcoin full node that you control.

Bitcoiners

Let me begin this section by saying: the most important thing that the Bitcoin network does is decentralize money. All other use-cases are secondary, including ordinal theory. The developers of ordinal theory understand and acknowledge this, and believe that ordinal theory helps, at least in a small way, Bitcoin's primary mission.

Unlike many other things in the altcoin space, digital artifacts have merit. There are, of course, a great deal of NFTs that are ugly, stupid, and fraudulent. However, there are many that are fantastically creative, and creating and collecting art has been a part of the human story since its inception, and predates even trade and money, which are also ancient technologies.

Bitcoin provides an amazing platform for creating and collecting digital artifacts in a secure, decentralized way, that protects users and artists in the same way that it provides an amazing platform for sending and receiving value, and for all the same reasons.

Ordinals and inscriptions increase demand for Bitcoin block space, which increase Bitcoin's security budget, which is vital for safeguarding Bitcoin's transition to a fee-dependent security model, as the block subsidy is halved into insignificance.

Inscription content is stored on-chain, and thus the demand for block space for use in inscriptions is unlimited. This creates a buyer of last resort for all Bitcoin block space. This will help support a robust fee market, which ensures that Bitcoin remains secure.

Inscriptions also counter the narrative that Bitcoin cannot be extended or used for new use-cases. If you follow projects like DLCs, Fedimint, Lightning, Taro, and RGB, you know that this narrative is false, but inscriptions provide a counter argument which is easy to understand, and which targets a popular and proven use case, NFTs, which makes it highly legible.

If inscriptions prove, as the authors hope, to be highly sought after digital artifacts with a rich history, they will serve as a powerful hook for Bitcoin adoption: come for the fun, rich art, stay for the decentralized digital money.

Inscriptions are an extremely benign source of demand for block space. Unlike, for example, stablecoins, which potentially give large stablecoin issuers influence over the future of Bitcoin development, or DeFi, which might centralize mining by introducing opportunities for MEV, digital art and collectables on Bitcoin, are unlikely to produce individual entities with enough power to corrupt Bitcoin. Art is decentralized.

Inscription users and service providers are incentivized to run Bitcoin full nodes, to publish and track inscriptions, and thus throw their economic weight behind the honest chain.

Ordinal theory and inscriptions do not meaningfully affect Bitcoin's fungibility. Bitcoin users can ignore both and be unaffected.

We hope that ordinal theory strengthens and enriches bitcoin, and gives it another dimension of appeal and functionality, enabling it more effectively serve its primary use case as humanity's decentralized store of value.

Contributing to ord

Suggested Steps

- Find an issue you want to work on.

- Figure out what would be a good first step towards resolving the issue. This could be in the form of code, research, a proposal, or suggesting that it be closed, if it's out of date or not a good idea in the first place.

- Comment on the issue with an outline of your suggested first step, and asking for feedback. Of course, you can dive in and start writing code or tests immediately, but this avoids potentially wasted effort, if the issue is out of date, not clearly specified, blocked on something else, or otherwise not ready to implement.

- If the issue requires a code change or bugfix, open a draft PR with tests, and ask for feedback. This makes sure that everyone is on the same page about what needs to be done, or what the first step in solving the issue should be. Also, since tests are required, writing the tests first makes it easy to confirm that the change can be tested easily.

- Mash the keyboard randomly until the tests pass, and refactor until the code is ready to submit.

- Mark the PR as ready to review.

- Revise the PR as needed.

- And finally, mergies!

Start small

Small changes will allow you to make an impact quickly, and if you take the wrong tack, you won't have wasted much time.

Ideas for small issues:

- Add a new test or test case that increases test coverage

- Add or improve documentation

- Find an issue that needs more research, and do that research and summarize it in a comment

- Find an out-of-date issue and comment that it can be closed

- Find an issue that shouldn't be done, and provide constructive feedback detailing why you think that is the case

Merge early and often

Break up large tasks into multiple smaller steps that individually make progress. If there's a bug, you can open a PR that adds a failing ignored test. This can be merged, and the next step can be to fix the bug and unignore the test. Do research or testing, and report on your results. Break a feature into small sub-features, and implement them one at a time.

Figuring out how to break down a larger PR into smaller PRs where each can be merged is an art form well-worth practicing. The hard part is that each PR must itself be an improvement.

I strive to follow this advice myself, and am always better off when I do.

Small changes are fast to write, review, and merge, which is much more fun than laboring over a single giant PR that takes forever to write, review, and merge. Small changes don't take much time, so if you need to stop working on a small change, you won't have wasted much time as compared to a larger change that represents many hours of work. Getting a PR in quickly improves the project a little bit immediately, instead of having to wait a long time for larger improvement. Small changes are less likely to accumulate merge conflict. As the Athenians said: The fast commit what they will, the slow merge what they must.

Get help